Tranquility by Theodore

A Review of Laura Vanderkam's "Tranquility by Tuesday" Through the Eyes of Theodore Roosevelt

Ever since I downloaded 168 Hours as an e-book in 2019 out of boredom and a lack of Ancestry story assignments, I’ve been a fan of Laura Vanderkam. I’ve read almost every single one of her books, which I’ve found useful in thinking about time management in my own life.

Thus when I was given the opportunity to read and review her book Tranquility by Tuesday in advance of the date it comes out (October 11), I jumped on it. Of course, Missing Pieces is a newsletter about the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, so I can’t just write a generic review of Tranquility by Tuesday.

Instead, I’m going to look at the tenets of Laura’s book from the lens of Theodore Roosevelt and see how well he did in keeping the nine principles. I’d encourage you to pre-order a copy of the book yourself and see how well you fare in comparison to our 26th president.

To figure out what TR’s timesheet might have looked like, I relied heavily on the primary sources available in the Theodore Roosevelt Center Digital Library. Sometimes the material was clear, although other times, I had to hazard my best guess. Without further ado, here’s Tranquility by Theodore!

Give yourself a bedtime

It’s unclear how TR felt about bedtimes. According to a quotation available on the Theodore Roosevelt Center website, he told Henry Cabot Lodge in an 1885 letter that he had been in the saddle working from 2:00 a.m. to 8:15 p.m. According to the Center, “Throughout Roosevelt’s career . . . he kept hours not too dissimilar from his time in North Dakota,” which would suggest that he wasn’t too keen on a bedtime.

However, in a 1909 letter to his son Ted, TR notes he and his wife Edith were at least in bed by 2:30 a.m. and likely before:

“[Mother and I] were waked up half past two by a most uncanny noise — apparently a thumping and shrill grunting in some remote part of the house. It was of course evident that it was Ethel and Kermit, with the house guests (about a dozen in number) doing something, but what it was at first impossible to imagine.”

Once TR figured out where they were, he recounts what happened next:

“I told them to stop at once and go to bed, but did not speak very severely, and in answer to a request from Ethel said they could go down and each get an apple in the pantry. By the time we reached the foot of that flight of stairs we encountered Mother in a most warlike mood, and the offenders were instantly smitten hip and thigh.”

I’m of the opinion that even if TR didn’t have a bedtime, Edith certainly did! In this case, it’s probably better to follow in Edith’s footsteps than in TR’s.

Plan on Fridays

Whether TR planned on Fridays was hard to determine. My best guess is that he likely did some sort of planning on Fridays because during the week of February 8-14, 1903, he sent significantly fewer letters and held fewer meetings on that day, which I determined thanks to this visualization made by Chloe Elder.

Even if TR didn’t plan on Fridays, it’s clear that he thought ahead and knew what he wanted to do. As another favorite author of mine, Cal Newport, author of Deep Work, Digital Minimalism, A World Without Email, and others, noted in a podcast interview:

“But something I consistently discover is that high achievers are often echoing the Roosevelt approach, which is ‘I want to actually allocate my attention,’ which means when you look at a particular day, you're not making a task list; you're blocking off your hours. What am I doing during this half hour? What am I doing during these three hours? You have so much attention to give in a day; you're trying to find the optimal allocation. They also think about this on higher scales. What am I doing this week? Oh, Wednesday is the day that I'm going to have a lot of downtime in the morning, so that's when I'm going to really get after this project. And so that idea of thinking about ‘I have, whatever it is—12 hours of attention to allocate in a day, some of those hours are going to be higher intensity than others, depending on where they fall; how do I get the biggest return on that attention?’ That's an incredibly powerful productivity hack.”

Edward Morris concurs in The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt: “Iron self-discipline had become a habit with [TR], and he plotted every day [in college and likely his whole life] with the methodism of a Wesleyan minister.”

Move by 3 p.m.

As an intern at the TRC, I read over two thousand documents related to TR. Roosevelt wrote countless letters scheduling appointments, including a pattern I started to notice. Often, he would ask individuals to go horseback riding with him in the afternoon. If he wasn’t riding a horse during the week, he was playing tennis.

Sometimes it was after 3 p.m., so not officially within the time limit of the rules, but many times it was before. In this 1904 letter to Stewart Edward White, TR invites him for lunch on Tuesday at 1:30 p.m. followed by “a good ride that afternoon.” The next day also looked similar:

“On Wednesday afternoon we will either walk or ride or exercise with the Japanese wrestlers, just as you wish.”

In case you were wondering if TR’s exercise was just limited to Stewart Edward White’s visit, he discusses his routine in a 1907 letter to Kermit:

“This week has past in a rather uneventful way. I have again been very busy. Have had a couple of afternoons’ tennis and a couple afternoons’ riding. It is not the slightest use, however, of my attempting to keep in such physical trim as would permit me to take any violent exercise, for I simply have not the time.”

Even if you’re like TR and don’t have the time for “violent exercise” and your “physical trim” isn’t quite what you would prefer, it’s still beneficial to move by 3 p.m. While you might not be able to ride a horse—or play tennis for that matter—before 3 p.m., surely you can follow in TR’s footsteps by getting outside for walk.

Three times a week is a habit

As we’ve seen already, TR regularly exercised typically more than three times a week, so he definitely maintained that habit. However, another habit he fostered was reading. He read on average one book every single day. Even when he traveled to Africa and the Amazon, he brought books with him, as he considered them essential companions.

I also remember how many letters I cataloged as an intern where TR thanked someone for a book or someone asked TR to read a book. If you want to get a taste of the books he read, Karen Sieber put together a reading timeline of all of TR’s mentions of books and reading from his first presidential term.

I imagine there were days TR didn’t get to read as much as he wanted to, but knowing that he got in some reading at least a few days a week certainly reminded him that he was in the habit of reading. Are you in the habit of reading like TR?

Create a back-up slot

I’m least confident that TR lived by this principle with how much he crammed into his daily life. For example, in a 1902 letter to John Campbell Greenway, he states:

“It is not possible for me to alter the schedule. You see to throw out one date would mean to dislocate twenty or thirty others.”

Similarly, TR tells Edward Kemeys in a 1904 letter that he can’t visit Kemey’s studio due to his busy schedule:

“I am afraid I shall have to give up calling at your studio. My experience is that my work goes on increasing in weight here, and I simply have no moment I can call my own.”

However, even if TR didn’t create a back-up slot, he managed to fit all of his priorities into his busy life—family, reading, exercise, church, and professional obligations—so I say that he wasn’t doing too badly.

One big adventure, one little adventure

Unsurprisingly, TR was a fan of adventures. To draw this conclusion, one need only consider his most famous trips: ranching/hunting expeditions out west in the Dakota territories, his African safari from 1909 to 1910, and of course his Amazon Adventure down the River of Doubt in 1914. For more information about TR’s love of nature, I’d recommend Darrin Lunde’s The Naturalist.

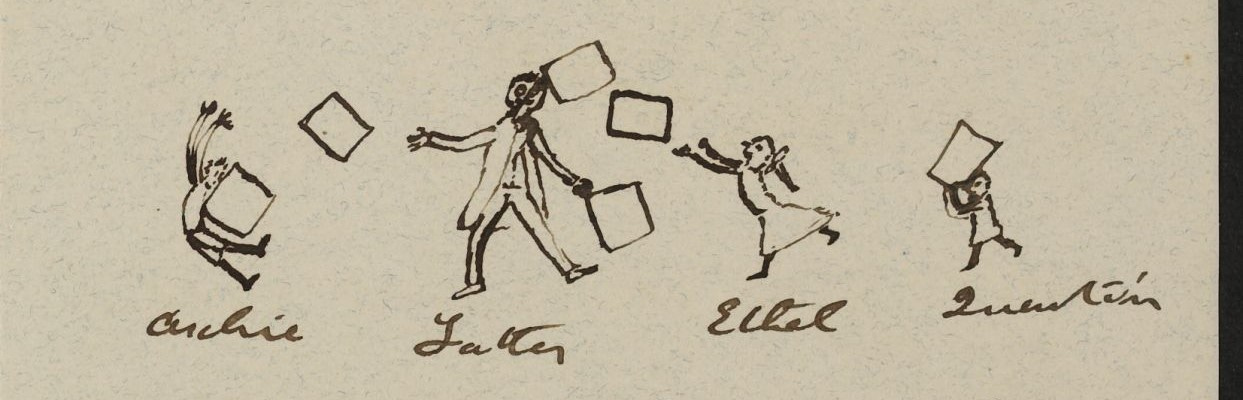

However, you might not know that TR enjoyed smaller adventures as well. One of my favorite discoveries as an intern with the Center was a handwritten letter from TR in which he illustrated a pillow fight with his kids at the White House.

Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Kermit Roosevelt. Theodore Roosevelt Collection. MS Am 1541 (62). Harvard College Library. Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University.

“Pillow fight with sofa cushions at White House. The effort to put glasses on father makes him look a little like an owl; and the realistic attempt to reproduce Ethel’s pigtail & ribbon is not wholly successful.”

We often think of TR as the president with the bully pulpit, but we don’t often reflect on his playful side, which I assure you appears regularly in his personal letters throughout his life.

He knew how to have a good time from seemingly small adventures to much larger ones. If you’re interested in reading more about TR’s adventures with his children, I’d encourage you to check out his book, Letters to His Children.

Take one night for you

As president, it was obviously hard for TR to set aside consistent time for himself. However, as his schedule for the week of February 8-14, 1903 reveals, he reserved Sunday for family time, a practice he appears to have adopted other weeks as well.

According to Jon L. Brudvig in “Theodore Roosevelt and the Joys of Family Life” in A Companion to Theodore Roosevelt, the Roosevelt family often visited Rock Creek Park most Sundays. Obviously, going out with the family isn’t quite taking one night for you, but TR seems to have set aside one day a week to take a break from the duties as president, so he recognized the importance of guarding time for himself.

Batch the little things

Again, this principle was also a little hard to determine, but for the amount TR was able to accomplish—he wrote a scholarly article about Irish mythology published in The Century Magazine during his presidency—suggests that he didn’t waste time. He wasn’t sitting through one-hour meetings just beside they were scheduled, for example.

Going back to the week of February 8-14, 1903, in some cases, he held as many as eight meetings in one hour, meaning the meetings were an average of just seven-and-a-half minutes each. If that isn’t batching the little things, I don’t know what is!

Effortful before effortless

Unsurprisingly, TR was a fervent proponent of “effortful before effortless.” In fact, I feel confident that this tenet would be his favorite. TR advocated extensively in favor of the strenuous life for both men and women.

Although he certainly had higher expectations for his sons regarding physical abilities, TR expected his daughters to be strenuous as well. TR’s address at Groton School in 1904 discusses the qualities that make a decent boy, including effort:

“The life that is worth living and the only life that is worth living is the life of effort, the life of effort to attain what is worth striving for.”

He states his support of “effortful over effortless” even more directly in an 1899 speech: “In this life we get nothing save by effort.” I think Laura Vanderkam would agree.

In closing, whether you’ve read one of Laura Vanderkam’s books before or not, Tranquility by Tuesday is worth a read, especially now that you’ve had the opportunity to read my review, Tranquility by Theodore.

If you decide to purchase Laura’s book or reserve it from the library, let me know by leaving a comment or replying to this email. I’d love to have a virtual book club meeting to compare notes!

I reserved Tranquility by Tuesday at the library and today it is finally available! I am looking forward to reading it! I would not have known about it without your blog!