Happy March! I’m delighted to coauthor this month’s Missing Pieces issue with my sister, Rebekah Slonim, author of Strike-Through, an editing newsletter, in honor of National Proofreading Day just two days from now on March 8.

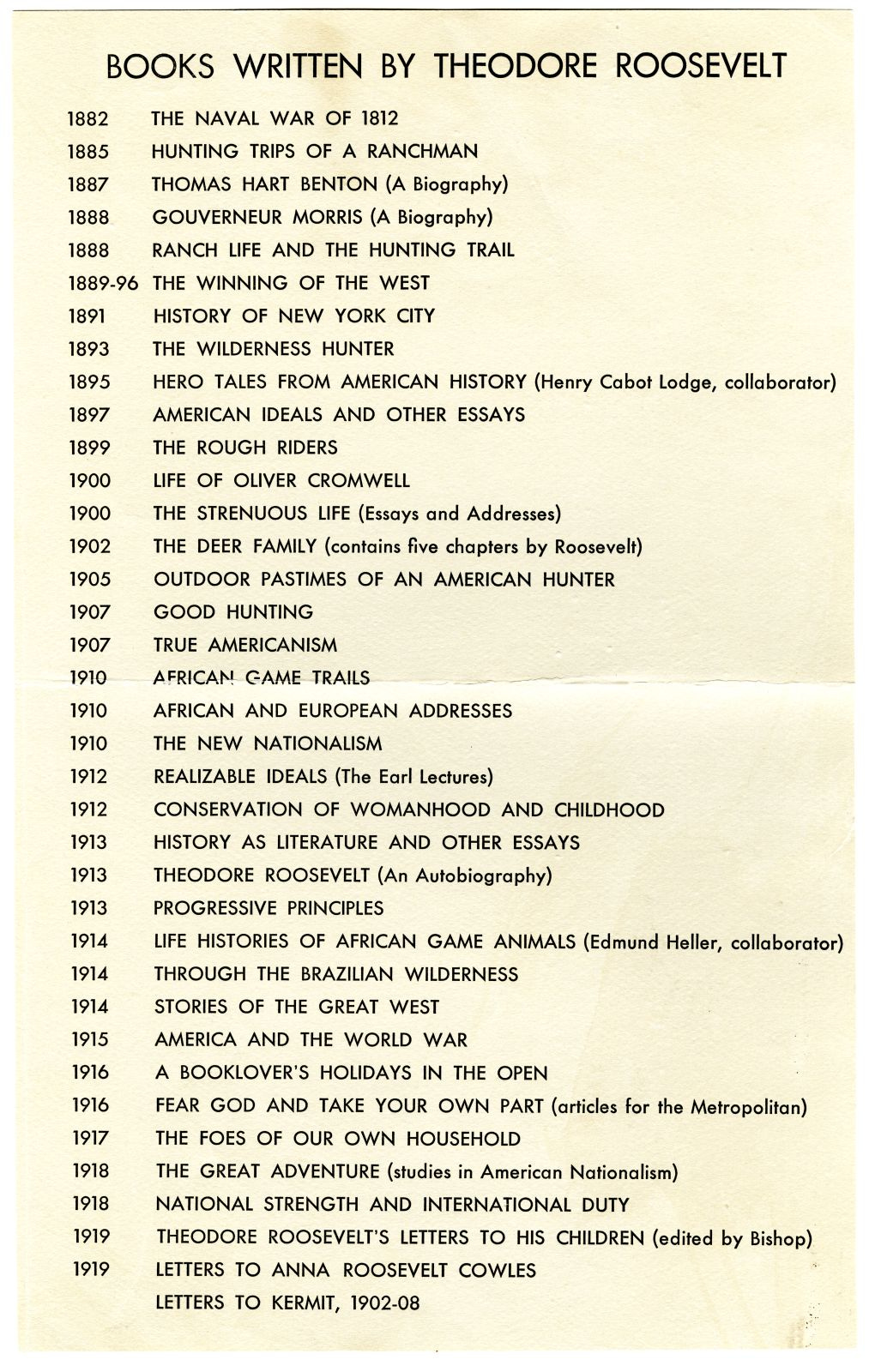

Source: Books written by Theodore Roosevelt. 1958 Theodore Roosevelt Centennial Symposium. Dickinson State University. Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University.

I (Rachel) will start with looking at Theodore Roosevelt as a man of letters. He wrote over 35 books as well as countless magazine articles and letters during his sixty-year lifetime.

I will focus in particular on a book TR wrote during World War I, Fear God and Take Your Own Part, before turning it over to Rebekah, who will briefly discuss page design components like typefaces and fonts.

Then—depending on which newsletter to which you subscribe—you’ll get a special section about two women with a direct connection to Fear God and Take Your Own Part in honor of Women’s History Month for Missing Pieces or a more thorough discussion of page design for Strike-Through.

If you don’t already subscribe to both of our newsletters but would like to, check out Missing Pieces (written by Rachel Lane) here and Strike-Through (written by Rebekah Slonim) here.

A Man of Letters

We all know Theodore Roosevelt as a president, a hunter, an explorer, and maybe even as a birdwatcher, a coffee drinker, and a fisherman thanks to Missing Pieces. But one aspect of TR that I haven’t really addressed before is his writing.

Throughout his life, TR was reading and writing. As he noted in an 1895 letter to his sister Anna, “I am still working up to my limit; for on the days I spend out here [at Sagamore Hill, his home in Oyster Bay, New York] I am busy with the closing chapters of my book . . .”

Roosevelt wrote over 150,000 letters throughout his life, which works out to 6.8 letters a day, as humanities scholar Clay Jenkinson noted in an article on TR’s literary mastery, and was rumored to read a book a day.

And he was a dedicated author of books and magazine articles throughout an active life and political career. Thanks to the hard work of the staff at the Theodore Roosevelt Center, you can see the extensive list of TR’s writings that are freely available online.

“Theodore Roosevelt was not only a prolific author, but a deeply involved one,” says Dr. William Hansard, a public historian at the Theodore Roosevelt Center. “He worked closely with publishers to design his books. He collaborated with them to choose typefaces, cover and spine designs, frontispieces, even the type of paper and its quality. He took photographs, or had them taken of him, that were either included as is or turned into illustrations by artists such as Frederick Remington. He even took cost into consideration, often assisting in the design of both affordable and luxury editions of his books.”

As one example of TR’s involvement in his books, Augustus Ralph Keller sent Roosevelt, who was then president, three different options for binding of “French crushed Levant in green, red, and blue” in 1902 and asked him to state his preference. (I’m not sure which one TR ultimately chose.)

Many of TR’s books focused on nature, the military, or history—and he was especially prolific during World War I, authoring five books related to that conflict. One of those books was Fear God and Do Your Own Part, a collection of articles originally published in the Metropolitan Magazine in which TR urged his fellow Americans to act on the principles of Americanism inside and outside of the country.

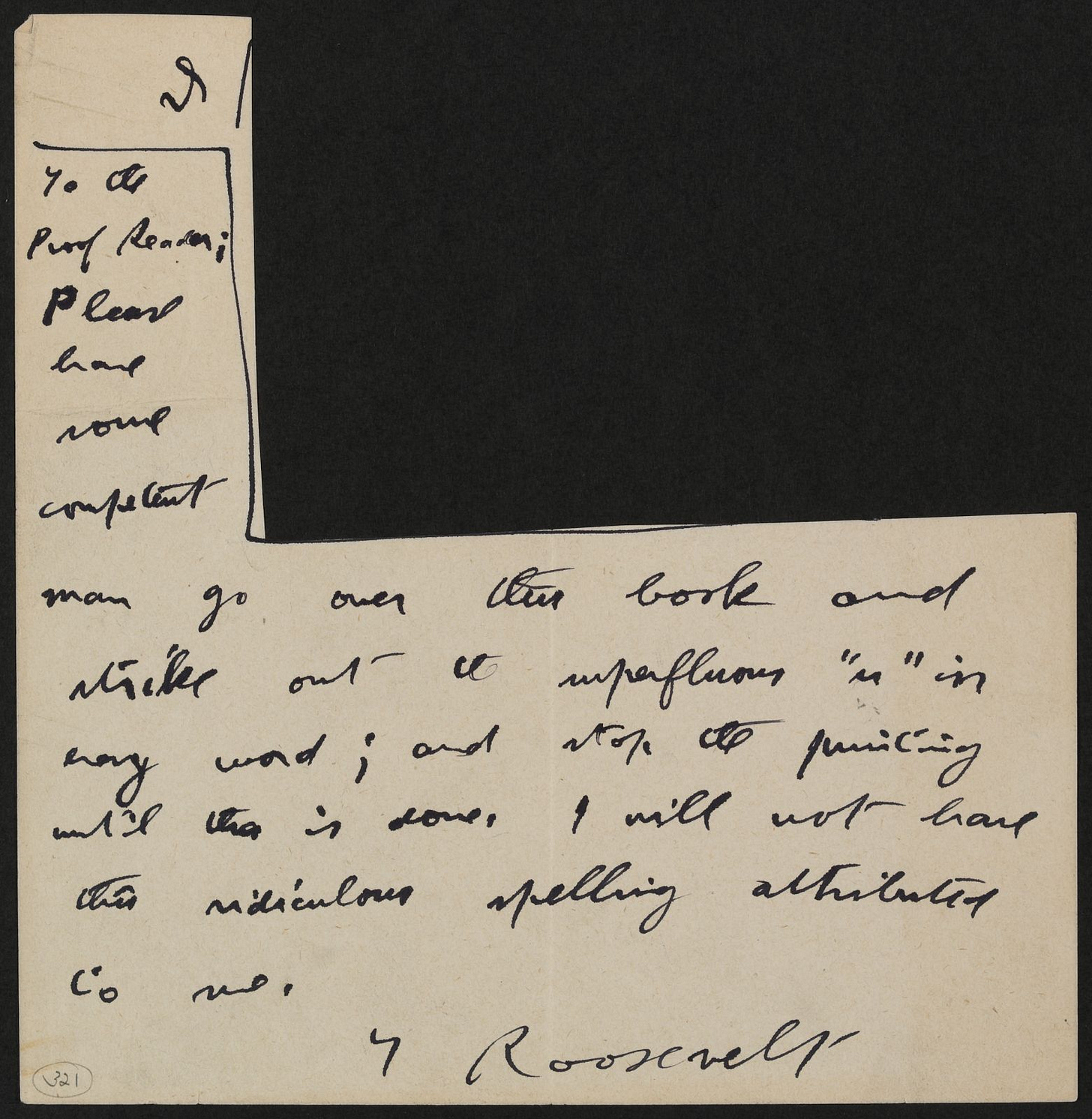

Before the book could get into the hands of the public, however, TR had strong words for the proofreader of his book when TR reviewed the proofs of Fear God and Do Your Own Part.

“To the proofreader: Please have some component man go over the book and strike out the superfluous ‘u’ in every word; and stop the publishing until this is done. I will not have this ridiculous spelling attributed to me.”

I assume the proofreader followed TR’s directions because the published version available on Google Books today doesn’t include any unnecessary u’s like in the word “honor.”

Over a hundred years have passed since the publication of Fear God and Take Your Own Part, and good proofreading, copyediting, and developmental editing are still just as essential—especially in this new world of AI.

Rebekah here. As we have seen, Teddy Roosevelt was very involved in the creation of his books. Writers, thinkers, and leaders who express deep, grand ideas tend to realize that the details that go along with these expression of those ideas—the commas that shape the sentences, the color of the spine and cover of the printed book—help to convey the meaning. Roosevelt and Lincoln are just two examples of politicians deeply invested in the minutiae of books and of language.

Some of the input that Roosevelt offered was more on the copyediting side, some on the design side, and some on the proofreading side.

A quick refresher on the difference between copyediting and proofreading, as people are sometimes confused about the difference. As I touched in my last issue, a simple way to remember and understand the distinction is that copyediting occurs before typesetting, and proofreading occurs afterward.

The Manuscript at the Copyediting Stage

The manuscript hasn’t yet been turned into a book at the copyediting stage. The book is in the final stages—no extensive rewriting is allowable at this stage—and it has chapter titles and section headings in place. But it doesn’t yet have a typeface (more on typefaces later), or running heads, or page numbers, or the other features that we associate with a published book. The copyeditor will make hundreds if not thousands of small changes to the notes and bibliography section to bring it into conformity with The Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS), and she will also make hundreds if not thousands of revisions to punctuation choices and wording choices, in the name of clarity, consistency, readability, and the dictates of house style or Chicago style. In modern-day publishing, at this point the book-to-be is a Word document that you scroll through.

Roosevelt’s instruction to delete superfluous u’s falls within the realm of copyediting. Although Roosevelt gave the directive at the proofreading stage, that’s really something that should have been fixed earlier, as it would necessitate many changes. Sometimes, global (i.e., manuscript-wide) issues like that aren’t caught until the proofreading stage, but it isn’t ideal, because the page numbers have now been set, and extensive changes can mean the page numbers need to be reflowed—an expensive fix.

The Manuscript at the Design Stage

After copyedits are completed, a designer typesets the book, which then gets sent to a proofreader.

Decisions about paper quality, trim size (the dimensions of a page), and number of illustrations are often made before copyedits, but the design stage is where those specifications are enacted.

Roosevelt choosing which color of French crushed levant he wanted to use for the binding of his book falls within the realm of design. (According to Merriam-Webster, “crushed levant” is “a smooth-surfaced strong flexible leather obtained by crushing a coarse-grained goatskin.”)

The Manuscript at the Proofreading Stage

At the proofreading stage, the book is a PDF of what the printed-out version will look like. The main job of the proofreader is to check for typos (there are always at least a few!) and to check the pages’ appearance. Are the running heads always in the same font? Are they correct, or has the running head for chapter 1 been placed at the top of all the pages in chapter 2 as well? Are there unnecessary line spaces anywhere? Is the font consistent for Heading 1s and for Heading 2s (e.g., is it always size 14 at the Heading 1 level and small caps for the Heading 2 level)?

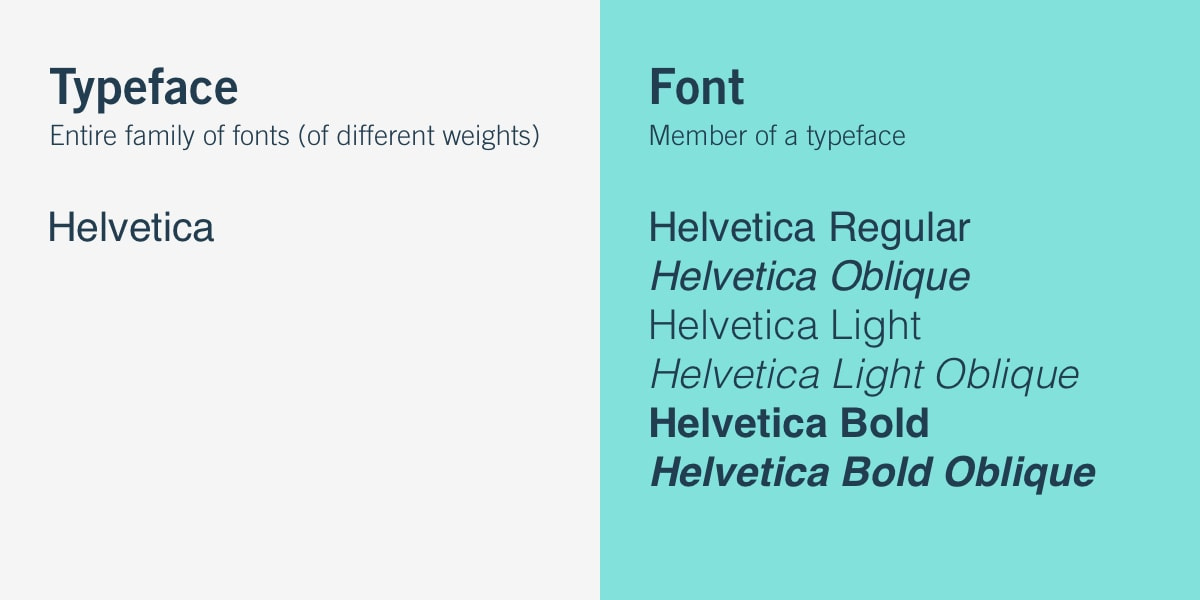

Quick note on “typeface” versus “font.” Traditionally, “typeface” means a family of fonts. It’s the more generic term. Debbie Berne explains in The Design of Books that “in the days of metal type,” “an author might go to a print shop and say, ‘I’d like my book set in Caslon’” (The Design of Books: An Explainer for Author, Editors, Agents, and Other Curious Readers [Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2024], 43). Caslon is the typeface.

But a font is the specifics: the individual member of the family. Berne’s explanation continues: “The printer might say, ‘. . . I’ve got two fonts: 10 point and 12 point” (Design of Books, 43). Another example: “Times New Roman” is the typeface, but “Times New Roman bold 12” is the font.

Now the terms are pretty much interchangeable: “In the digital age, the fonts we use are computer files. I don’t have stacked cases of metal type in my office, but thousands of files on my computer. . . . What was a useful difference in terminology has become, in most situations, irrelevant” (Design of Books, 43).

This graphic explains it better than I can:

Source: Career Foundry, “What Is Typography, and Why Is it Important?”

If Roosevelt looked through the page proofs to make sure the typeface/fonts had been applied correctly—and would make sense if he did, because he chose them—that would fall within the realm of proofreading.

Roosevelt devoted careful attention to the words and design of Fear God and Take Your Own Part, along with his other books, because he believed deeply in their message. And the message contained therein honored and inspired two specific woman, Julia Ward Howe and Ethel Roosevelt Derby.

Two Women Who Did Their Part

Back to Rachel. My interest in Fear God and Take Your Own Part goes beyond the interesting glimpse under the hood of TR’s involvement in his books. The book also is a fitting work to consider in March during Women’s History Month given its connection to Howe and Derby.

From the very beginning of the book, TR recognized the contributions of women, dedicating Fear God and Take Your Own Part to Julia Ward Howe, an abolitionist, social activist, and suffragist who wrote The Battle Hymn of the Republic and who died just a few years prior to the start of World War I.

Source: Julia Ward Howe. Wikimedia Commons

“This book is dedicated to the memory of Julia Ward Howe because in the vital matters fundamentally affecting the life of the Republic she was as good a citizen of the Republic as Washington and Lincoln themselves. She was in the highest sense a good wife and a good mother and therefore she fulfilled the primary law of our being. She brought up with devoted care and wisdom her sons and her daughters. At the same time she fulfilled her full duty to the commonwealth from the public standpoint. She preached righteousness and she practised [sic] righteousness. She sought the peace that comes as the handmaiden of well doing. She preached that stern and lofty courage of soul which shrinks neither from war nor from any other form of suffering and hardship and danger if it is only thereby that justice can be served. She embodied that trait more essential than any other in the make-up of the men and women of this Republic the valor of righteousness.”

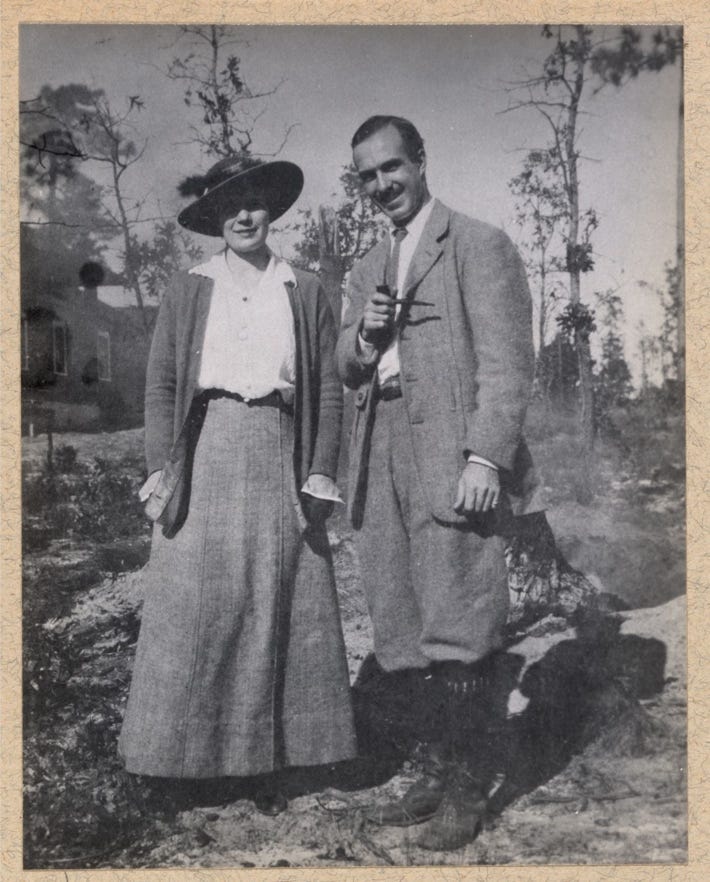

Although not mentioned in the book itself, TR’s daughter Ethel Roosevelt Derby was the embodiment of taking action to promote the American way of life during World War I. She was the first person in her family to go overseas during the First World War, working as a nurse alongside her husband, who was a physician, in the American Ambulance Hospital.

TR vacillated between pride for his daughter’s willingness to serve overseas and concern for her wellbeing, though there was more pride than concern overall. As he wrote in November 1914 to the Derbys, “I know you are having a hard time, of wearing anxiety and sorrow and effort; but I am very proud of you both and very glad that you have been able to go over and to do your part – and a portion of this nation’s part – in helping those who suffer in this terrible cataclysm.”

Despite TR’s best efforts to join the war effort—he volunteered to lead the Rough Riders again—President Woodrow Wilson rejected TR’s plan. Although TR was bitterly disappointed, he decided to do what he did best (write!) and advocated for American involvement in the war and the Preparedness Movement.

Ultimately, all of TR’s children and most of their spouses served at some point during World War I. His youngest son Quentin even died during the war, shot down by a German plane on July 14, 1918.

To cope with such a devastating loss, TR turned to the pen, writing a tribute to his son for the Metropolitan Magazine entitled “The Great Adventure,” which was later reprinted in a book of the same title—TR’s last book before his death in 1919. As Lord Charnwood records in Theodore Roosevelt, “He was told that he had never written so well before, and answered, ‘Ah, that was Quentin’” (209).

TR dedicated much of his free time to reading and writing. He enjoyed all kinds of books from history to children’s stories. Vote for your favorite genre in the poll below!

When I read this, I remember just how well-rounded TR was in his lifetime. He certainly sets the bar!