Happy September, and welcome to football season! Attentive readers may notice that this Missing Pieces issue is a week late.

Last week I was in North Dakota attending Dickinson State University’s annual Theodore Roosevelt Symposium, which was about TR and conservation this year. As you can imagine, that kept me quite occupied, so I decided to send out September’s issue this Wednesday instead.

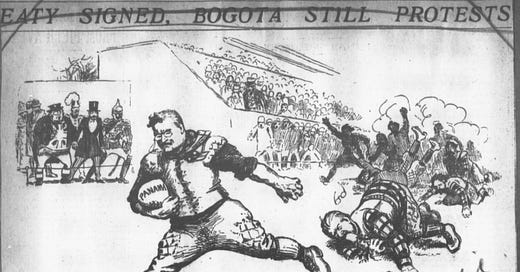

Source: Panama as a football. Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University.

As some of you may know, I come from a family of football watchers (a divided house—my dad is a Bengals fan, and my mom is a Steelers fan), so the fall always makes me think of football Sundays.

What you might not know is that Theodore Roosevelt had a special connection to the game of football. Although I had known about this connection since my internship with the Theodore Roosevelt Center, I hadn’t done much research about it.

When Missing Pieces reader Jonny brought it to my attention again a couple months ago, I knew I wanted to start football season off with a Missing Pieces issue devoted to football. Thank you, Jonny, for the excellent idea! (If other readers have ideas for upcoming newsletter issues, please pass them my way!)

In short, TR loved football. He saw it as a good, manly sport. In a 1895 letter to the “Father of American Football,” Walter Camp, TR—then a US civil service commissioner—delineated his appreciation for football, stating, “Of all games I personally like foot ball best, and I would rather see my boys play it than see them play any other.” TR’s wish came true. All four of his boys—Ted, Kermit, Archie, and Quentin—eventually played the game.

Source: Theodore Roosevelt Jr. injured. Prints and Photographs division. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University.

While TR frowned upon his daughters Alice and Ethel playing the sport, that didn’t stop his daughter Ethel from watching it—or teaching it! The January 1909 issue of The Delineator, an American women’s magazine, noted that Ethel—then a teenager—taught her Sunday School class of ten Black boys averaging ten years of age football on Saturdays:

“On Saturdays, through the fall, she also taught them football, taking the ten out on a vacant lot, herself umpiring the game, and afterward serving a picnic lunch from a White House hamper.”

Source: Ethel Roosevelt at football. Bain News Service. Library of Congress.

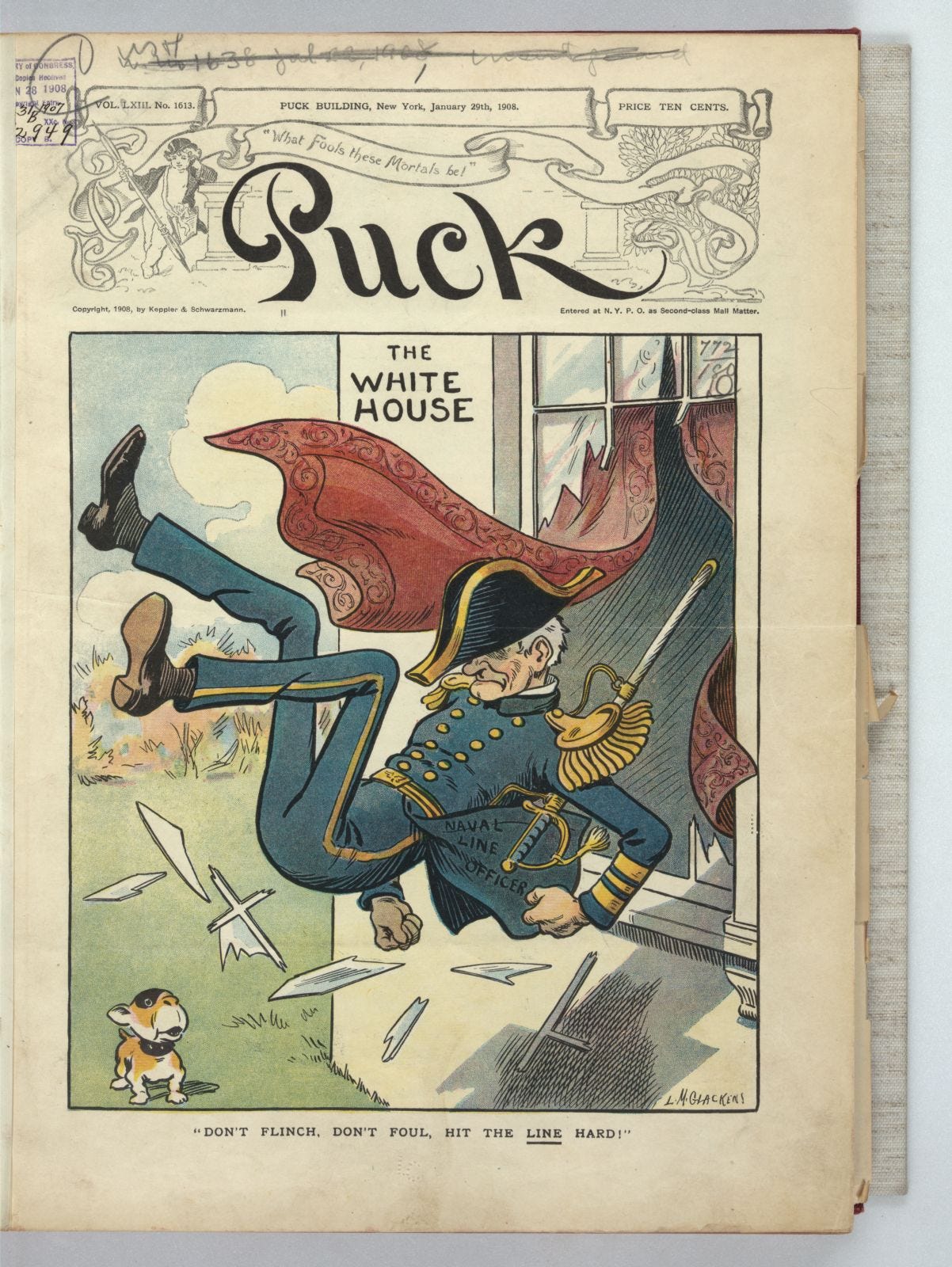

TR himself even used a football phrase as one of his life rules. As he noted in a 1903 speech in Salina, Kansas, “[T]he best advice I could give to use in the great game of life is the advice upon which a football player acts – don’t flinch, don’t foul, and hit the line hard. This counts in life just as it does in sports.”

Source: “Don't flinch, don't foul, hit the line hard!” Prints and Photographs division. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University.

When President Charles Eliot of Harvard University started to call for outlawing the sport due to its injuries, TR strongly disagreed. In his 1895 letter to Camp, TR indicated his disgust with Eliot’s attitude toward football, though TR agreed with the need to “do away with needless roughness in playing.” TR believed rough play was acceptable as long as it was “confined within manly and honorable limits.”

Ten years later, TR spoke at a meeting of Harvard alumni in June 1905 urging coaches and industry leaders to address the brutality. He even went a step further in the fall.

On October 9, 1905, TR invited six men—including the football coaches of Yale, Harvard, and Princeton—to the White House to encourage them to clean up the game. Eighteen players died in 1905 alone, and TR’s son Ted was injured that season—many believed he had been targeted.

The meeting was a success. As TR summarized in an October 11, 1905, letter to Nicholas Murray Butler, president of Columbia University, the six men drew up the following memorandum:

“At a meeting with the President of the United States it was agreed that we consider an honorable obligation exists to carry out in letter and in spirit the rules of the game of foot ball relating to roughness, holding and foul play, and the active head coaches of our universities being present with us pledge themselves to so regard it and to do their utmost to carry out that obligation.”

Source: Random Rhymes and Odd Numbers by Wallace Irwin (1906). Google Books.

TR’s meeting even entered the public consciousness through a plethora of political cartoons and even a poem. In a nod to TR’s assistance in arbitrating a peace between Russia and Japan during the Russo-Japanese War, Wallace Irwin included the poem “Another Peace Conference” in his 1906 book, Random Rhymes and Odd Numbers, that addressed TR’s 1905 meeting of football coaches. The entire poem is entertaining, but I especially like the beginning.

“‘Come here, come here, football play-ers,

Ye coaches wild and tough!

Why do ye slug and gouge and chug

And raise a house so rough?’

So up spake bluff King Theodore

In something more than bluff.”

Less than six months later, the American Intercollegiate Football Rules Committee met on April 2, 1906 to adopt a revised set of rules for the game. Many believe these safety reforms helped save the future of football due in part to TR’s efforts. In acknowledgement of TR’s contributions to the safety of football, the NCAA’s highest honor—the Teddy—is named after him.

No matter what team you root for or how successful your fantasy team is, you can thank TR for saving the sport! If you’re interested in learning more about TR and football, I invite you to visit former TR Center intern Christa Daugherty’s timeline.

TR supported football at all levels from high school to college. What’s your favorite level of football to watch?

Gotta love TR’s broad interests.

Having a healthy motivation for physical exercise is very important!